News and updates

News and updates from the project, writings about kelo trees

Ramboldia elabens

After years of work, the first scientific publication of the Kelo project is ready! The article concerns lichens growing on the surface of kelo trees, and the goal was to investigate how the lichen communities change over the decades or centuries that dead Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) may remain standing after death. The bark usually falls off during the first couple of decades after death. As the wood is exposed, the substrate provided by the tree becomes very different, and the development of the lichen community on the wood begins from scratch.

The data consisted of 331 standing dead trees, from which we recorded lichens up to a height of two meters, and whose year of death we determined from annual rings. These 331 trees formed a chronosequence that covered 275 years from tree death. The lichen study included only debarked trees. A similar, but more extensive chronosequence that includes also bark-covered dead trees, will be used in later studies of the project to address other research questions.

Time since tree death was found to be a central factor for lichens. Nearly all the observed lichen species were associated with either fresh, intermediate or long-standing standing dead trees. The number of observed species increased with time since tree death but no longer increased at 90 years from death. These community changes occurring over time were probably related to changes in the wood surface caused by weathering and decomposition.

Chaenothecopsis fennica

A total of 135 lichen species were recorded in the study. Standing dead pine trees are quite a lichen rich substrate, and especially in pine-dominated boreal forests, a considerable portion of lichen diversity is found on deadwood, and standing deadwood in particular. From the species observed in this study, 33 are considered deadwood-dependent, meaning that most of the species occurring on the wood of standing dead trees may occur also on the bark of living trees.

Species that are dependent on deadwood and associated with long-standing kelo trees are of special interest. Our study identified 11 species of this kind. If species that were missing or rare in our data are accounted for, there probably are many more species like that. These species have declined steeply with the disappearance of kelo trees from the managed forest landscape, and accordingly, nearly all of them are nationally red-listed.

Lichens dependent on long-standing kelo trees are a great challenge for conservation and restoration. At the moment it is not known whether is possible to promote or expedite the formation of long-standing kelo trees. We are aiming to provide answers also to these questions during the Kelo project. In any case, the development of the substrates required by these specialized species will take several decades if not centuries. The challenges related to restoration emphasise the significance of the remaining old-growth forests.

Calicium denigratum

Some lichen species specialized to long-standing kelo trees:

- Ramboldia elabens

- Chaenothecopsis fennica

- Chaenothecopsis viridireagens

- Calicium tigillare

- Calicium denigratum

- Pycnora xanthococca

- Micarea elachista

- Microcalicium ahlneri

Read the whole scientific article here.

Reference:

Nirhamo A, Santos P, Günther M, Kouki J, Aakala T. (2026) Community dynamics of lignicolous lichens on standing deadwood in a 275-year chronosequence. Oikos: e11835.

Text written and photographs by Aleksi

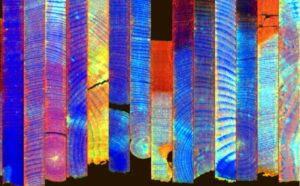

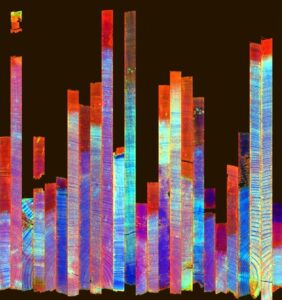

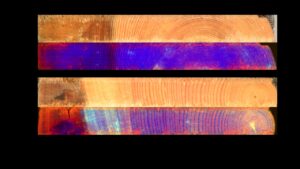

Some hyperspectral images of pine deadwood.

Back from the dead! This site has been quiet for a while, as we have been immersed into our methods and analyses. So, don’t worry, behind the scenes a lot of the scientific work is brewing and once the results start kicking in, we have a lot more to talk about.

In the meanwhile, in this post I want to give you a glimpse into my methods. In the kelo project I am studying the chemical composition of Scots pine deadwood, to find out what makes kelo trees have their unique longevity. There must be a reason, why the decomposers don’t have a good appetite for kelo wood. My methods might seem a bit much, as they delve into several fields of science, but I will try to introduce you gently into the fascinating world of hyperspectral imaging. It explores light (electromagnetic radiation), also beyond what we can sense with our bare eyes. This light holds information that visible light cannot convey.

I am talking about near infrared light, radiation that has longer wavelengths than visible light. Near infrared (NIR) radiation was found already in the 19th century, but it wasn’t really used for research until the 20th century. Then scientists developed near infrared spectroscopy, where one captures how an object absorbs and correspondingly reflects near infrared light into a near infrared spectrum. This infrared spectrum is valuable as it contains information about the chemical constituents and structure of the object. You see, molecular bonds in organic compounds (so bonds between carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen), they vibrate differently. They might stretch, twist, wag, rock, and scissor (sounds like a dance battle that turns into rock-paper-scissors!) and the movements absorb energy differently. Thus when we illuminate an object and record the infrared radiation that comes back to the detector, we see signs of this movement in the shape of the spectrum (as some infrared radiation has been absorbed and some not). Thus spectroscopy can be used to study the chemical composition of an object.

Increment core samples of pine deadwood side-by-side, so that the pith is always at the bottom and the tree surface at the top.

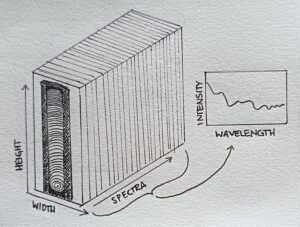

However, NIR spectroscopy doesn’t capture how the chemical composition varies spatially, as it is limited to a small region. For example wood is very variable material, so a lot of information might stay in the dark. This is where hyperspectral imaging comes handy, as it captures also the spatial information, by recording an infrared spectrum to each single pixel in the image. Hyperspectral imaging produces a hyperspectral cube that contains spatial and spectral information. Visualize a cube, where the height and width of the cube is formed by a collection of pixels like in a regular 2D-photograph, but then the cube also has the spectra of pixels as its depth. So it is like a stack of images of the same object that only differ by wavelength (see illustration below). Whereas a pixel in regular RGB-image contains information about the proportion of three spectral channels (red, green, blue), a pixel in hyperspectral cube usually contains information about over 200 spectral channels.

Illustration of a hyperspectral cube, where each wavelength can be used to make a picture of the sample.

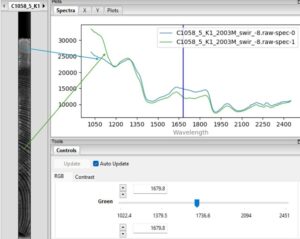

Below this chapter is a screenshot taken from the software I use, where I have opened the hyperspectral cube of one of my samples. In the small image on the left you see the sample in a greyscale image, and in this picture all pixels show how intensively light is reflected at 1680 nanometres. But on the right there are two complete spectra from two pixels I selected from sapwood and heartwood of this samples (arrows show approximately the regions). This specific camera captures wavelengths from 1000 to 2500 nanometres, way past our vision. You can see how the spectra are somewhat different in sapwood and heartwood, as they contain different amounts of for example lignin and extractives (note here, spectrum doesn’t only indicate chemical composition, but it can also show physical differences in the sample, like how wood fibres are positioned and what is the cell size and cell wall thickness). The blue vertical line implies the wavelength 1680 nm that is visualized in the grayscale image – this specific greyscale image is only showing a very small portion of all the information the data cube contains, as similar image could be made for all the wavelengths between 1000-2500 nm! It is also possible to make a false colour image by assigning red, green and blue to three wavelengths of your choice: that’s how you get an image like the two images at the start of this blog post and in the last image.

Different ways to view hyperspectral cube.

So hyperspectral imaging produces a lot of data, and I have these data cubes for 613 samples! Yet, the information in the NIR spectrum is quite hard to separate, as same wavelengths can be impacted by several factors. This is why when making this kind of research, we need to also have a reference method, that records the exact chemical information, that we can then use to make sense of what is relevant in the spectra for us. In the autumn I sent 200 saw dust samples to high resolution mass spectrometry analysis (very expensive machine in the chemical apartment, that I surely would not even be allowed to lightly touch). These saw dust samples were taken from the increment core samples I had already imaged during six months of winter 2023-2024. Once the chemistry data from mass spectrometry analysis is ready, we can start to build a model between hyperspectral- and mass spectrometry data. This model enables us to make chemical maps with just the hyperspectral data. Then we can show you how the chemical composition varies from pith to bark in a pine deadwood tree and how the trees differ from each other. And hopefully I can show you what a kelo tree looks like from the inside, also beyond what you could see with your bare eyes (image below can give an idea already). It has been fun and rewarding to learn this completely new method for me, where I get to mix forest sciences and ecology with chemistry and physics. Science at its best!

RGB-image and false colour hyperspectral image of two samples. Sample above has higher moisture content.

References:

ElMasry, G. M., & Nakauchi, S. (2016). Image analysis operations applied to hyperspectral images for non-invasive sensing of food quality – A comprehensive review. Biosystems Engineering, 142, 53–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2015.11.009

Manley, M. (2014). Near-infrared spectroscopy and hyperspectral imaging: non-destructive analysis of biological materials. Chemical Society Reviews, 43(24), 8200-8214. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4cs00062e

Text written by Tilla

Coring- and lichen squad

The summer of 2023 was the busiest fieldwork season for the Kelo-project. For two and half months we worked long days in North Karelia, Kuusamo, and Salamanperä collecting samples and data for PhDs and a master thesis. In addition other project members visited the site and did fieldwork for a shorter time.

For Pem, Tilla, Marie, Aleksi and Alina almost the whole summer was spent in the field defying bugs and unstable weather. Pem and Tilla cored kelos and other dead pines, to collect samples for dendrochronological and chemical analysis. Pem’s ambitious target was to sample roughly one thousand trees, and for Tilla the challenge lied in collecting different kinds of samples, of which most were taken from the base of tree that often was quite decomposed. It is not the easiest job to core deadwood! Luckily we had the pleasure of having our intern Marie helping us in mainly packing the samples and writing notes.

For Aleksi and Alina the focus was on the lichens on standing kelos. Aleksi collected information of every species on the trees or took samples of lichen species that needed further identification by a microscope or other method. Alina collected information about the lichen coverage on kelos, and this data she will use for her master’s thesis.

Lichen researchers at work

During the summer the research areas hosted also other project members. Our bird expert Philippe spend early mornings in the sites listening to birds singing. During one morning a brown bear passed by Philippe without noticing him, as Philippe was so quietly focused on listening! In September the fieldwork ended in inventory of wood-decaying fungi on kelos and other dead pines, as Panu and Jorma went to do their fieldwork in Salamanperä plots.

Our photography artists Ritva and Sanni joined us in the beginning of the summer to photograph the scientific fieldwork, and to plan their artistic project. And at the very end of the coring and lichen fieldwork, we had the pleasure of hosting Swedish colleagues for developing collaborations on research on kelos.

Enjoying a lunch break

Indeed, we had a busy fieldwork summer, but now the researchers have already started the preparing and analysing samples and data. Lots of work with a microscope, sanding, and imaging ahead!

Antrodia crassa

I found my very first Antrodia crassa in the year of 1999 from Tapionaho in Koitajoki. It was a significant event, not just for me, but for the survey of threatened polypore species in general, as by then, few A. crassa occurrences were known in the whole of Finland.

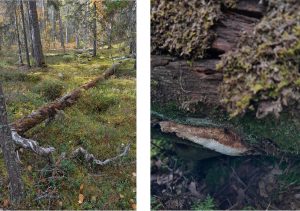

A. crassa grows only on fallen, well-decayed pine kelo trees, often by a mire. The sporocarp of the polypore hides under the pine trunk and resembles a white piece of soap.

For A. crassa to be found, the forest must have lived in peace and quiet for several hundred years. First, a pine seedling needs to sprout in a suitable location. Next, the tree must be able to grow several centuries into an elderly pine tree, and after its death, the tree must develop into a silverly kelo. Finally, after falling, the tree has to lie on the forest floor for decades until the wood material is decayed enough to host A. crassa.

Although the habitat might be suitable, the specialist might not find it. For the population of A. crassa to prosper, a fallen kelo needs to be surrounded by an extensive kelo pine forest. In this forest, the A. crassa spores will make their way to a new kelo trunk when the previous one becomes too decomposed. If there are not enough suitable kelo trees in the forest stand and other stands are not nearby, A. crassa likely disappears from the area.

After that one observation, no further A. crassa was found in Koitajoki. Outside conservation areas, where the forest is under 400 years old, the species cannot survive. In addition, the old-growth forest stands of conservation areas are very fragmented in the landscape and located far away from one another. If A. crassa becomes extinct in one forest stand, it is unlikely to be able to disperse there again, although old kelo logs might be there to give it a home.

This is why A. crassa has become an endangered species.

On the left a suitable kelo log for A. crassa and on the right A. crassa living on a kelo

Luckily, there are still many other polypore species that inhabit Koitajoki area.

Fallen spruces are decorated by Fomitopsis rosea and Amylocystis lapponica. A bright yellow Antrodiella citrinella may succeed on the trunks decomposed by Fomitopsis pinicola, and after Phellinus ferrugineofuscus, Skeletocutis brevispora and S. exilis may inhabit a spruce log. Under the trunk, you might even find a Skeletocutis stellae hiding.

Kelo logs in Koitajoki are still inhabited by Antrodia albobrunnea, Postia lateritia and Antrodia infirma. In addition, restoration burns and burning of logging sites have created suitable habitats for Dichomitus squalens and Erastia aurantiaca. Moreover, Gloeophyllum protractum, in turn, settles especially on the human-made duckboards.

Fallen aspen logs provide a home for Antrodia pulvinascens and A. mellita. After an Inonotus obliquus, the Chaga, has decayed a birch trunk, Antrodiella pallescens, Aporpium canescens and Gloeoporus dichrous can follow.

Polypores release nutrients from tree trunks for the use of other organisms. A well-decomposed log is a perfect seedbed for a tree seedling, and so the story starts from the beginning again.

Text is written by the Kelo-project’s Kaisa Junninen. The text was originally published in Pogostan Sanomat 2.2.2023.

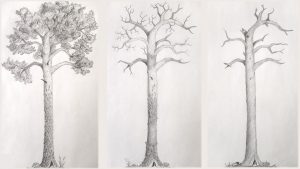

How kelo trees are formed is still poorly understood, but the evidence so far points to a long chain of events for a pine seedling to develop into a kelo. However, after a kelo forms, it may remain standing for centuries and hence with time, natural forests may gradually accrue large numbers of kelo trees in different stages of their development. Due to the long time spans involved, even a small human influence either directly on existing kelo trees, or to pine trees – the candidates for future kelo trees – may have an impact on the presence of kelo trees in a forest landscape.

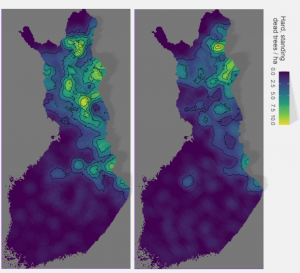

Modern forestry with rotation times up to 100 years or shorter is largely incompatible with the formation of kelo trees. However, in many regions kelo trees disappeared from the forested landscapes already prior to the onset of currently dominant forest management regime in Finland, which occurred in the 1950s. Using measurements from the national forest inventories, Kalliola (1966) studied the changes in the numbers kelo trees from the 1930s to 1960s, which encompasses this transitional period. His aim was to examine the naturalness of the Finnish forests for which the presence of kelo trees is one credible indicator (it should be noted that Kalliola uses measurements of all hard standing dead trees over 20 cm to estimate the density of kelo trees. He argues that other species than pine fall over relatively rapidly and represent only a minor share of the whole). The findings demonstrate clearly how kelo trees had disappeared from the southern and western parts of Finland already prior to modern forestry, but how they were a prominent structure in the forests of the Suomenselkä water divide in Central Finland, in the East, and in the North all the way to the subarctic treeline.

Kelo densities started to decline also in these regions, when forest management based on clearcutting reached these previously relatively untouched forests. While kelo trees were earlier used as firewood, the intensification of forest industries meant that kelo trees were also harvested for the pulp industries, which is visible especially well in the reduction the numbers of kelo trees in the southern Lapland.

Figure above presents the presence and density of hard, standing dead wood over 20 cm in diameter across Finland as measured in the 2nd and 4th national forest inventories (redrawn from Kalliola 1966), in 1936-38 and 1960-1963. Color and topography of the map describe regional average of kelo densities. Already in the 1930s these trees were rare in the South and in the West, but still abundant in the East and the North, and the Suomenselkä water divide in Central Finland. Kalliola’s research well shows how kelo densities declined by mid-1960s, after which greater densities were confined to the Northeastern Wilderness and the Inari region in the far North.

Although kelo trees are considered a feature typical to the North, this geographical distribution is largely due to human influence on forests. Kelo trees have earlier been an important part of forests throughout Finland, and they are still found wherever untouched forests still remain. This includes the Bialowieza forest in temperate Europe, much further South than their distribution in Finland.

Reference: Kalliola, R. 1966. The reduction of the area of forests in natural condition in Finland in the light of some maps based upon national forest inventories. Annales Botanici Fennici 3: 442-448.

Text is written and map is made by Tuomas Aakala, Kelo-project coordinator.

Scots pine turning slowly into a kelo tree

Would you like a short and sweet introduction into what we know about kelo trees so far? In this post, I would like to present you an online booklet that I made, called “Lifecycle of a kelo tree”. With illustrations and texts you get to follow the lifecycle of one Scots pine tree, from seedling to a fallen kelo log. You can access booklet by clicking here.

I was prompted to make this booklet after reading all kinds of texts about kelos. Texts online and in books often state things about kelos, that are not based on research, but seem to be passed on from text to text without any idea of the original source and its accuracy. So in this booklet I made, I wanted to use only published scientific articles, to tell you what we know about Scots pine and its kelo form based on research so far. I can tell you right now, that there are only a handful of articles on kelo trees! The aim is to update this booklet as we get our own study results which hopefully will fill the knowledge gaps of kelo trees and their formation.

Best regards, Tilla

Tuomas coring a kelo from one of our study plots in North Carelia in October

Last October, journalist Sampsa Oinaala joined us – Tuomas, Pem and Tilla – as we went to two of our study plots in the Cajander old-growth forest in Northern Carelia. We wanted to take some samples for preliminary analysis before the actual sample collection next summer, and Tilla and Pem also took the opportunity to practise their tree coring skills.

Sampsa followed our work and interviewed us as we travelled two hours from Joensuu. Based on that day and its discussions, Sampsa wrote a fine article about our research and kelo trees. It is now published in the Kone Foundation website, and you may read it by clicking here.

Calicium tigillare on an old fencepost. This species does not have pin-like fruiting bodies, but it forms a spore mass the same way as other calicioids. A similar-looking species called Calicium pinicola is known from Sweden and Norway, but unfortunately it does not occur in Finland. Photo: A. Nirhamo

Lichens are omnipresent in Finnish nature but taking notice of the full range of their diversity requires careful and detailed observation. Kelo trees, especially long-lasting ones, are also often full of diverse lichens.

In the summer of 2022, I surveyed a group of kelo trees in Patvinsuo national park in eastern Finland. I collected similar data from snags (standing dead trees) on logging sites formed from retained pines. The lichen communities on the kelo trees were highly species-rich: on average, 23 lichen species were found on the kelo trees, and one bore as many as 39 lichen species. Species richness was also rather high on snags on logging sites (avg. 18 species), but the species composition was distinctively different. Nearly all lichen species that specialize in growing on deadwood are small crustose lichens (also known as microlichens). In addition, larger generalist species and crustose lichens that also occur on bark may be found deadwood. The species assemblage on snags on logging sites consisted in a much larger extent of generalists, whereas the assemblages on kelo trees consisted of more specialized species. This is reflected for example in the occurrence of red-listed species: snags had, on average, 0,6 red-listed species, while kelo trees had on average 3,7 red-listed species, with 8 red-listed species on one kelo at the highest. Red-listed species often observed on kelo trees included Micarea elachista, Ramboldia elabens and Calicium denigratum. These numbers demonstrate the high importance of kelo trees to lichen diversity.

Calicium viride on the bark of Picea abies. The “pins” are the apothecia i.e. the fruiting bodies of the mycobiont, and they have developed an exceptionally long stalk. Another exceptional feature of these lichens is that the apothecia do not “shoot” the spores to be carried by the wind, instead the spores remain on top of the apothecium as a spherical spore mass. This way, the spores may be attached to woodpeckers or other birds and thus be dispersed to other trees with the birds. Photo: A. Nirhamo

However, at least in Patvinsuo the situation is worrisome, since it is evident that the kelo continuity of the areas, where I collected the data, is being disrupted. Because of logging operations completed before the founding of the national park, there are almost no large, old pines from which long-lasting kelo trees could form in the next decades. Scarce kelo trees may still be found in the area, and surveying these trees made me feel like an archaeologist studying ancient relics. These kelo trees may have originated from trees that were left as seed trees in previous loggings, or perhaps they were already dead at the time of the loggings. When the current kelo trees are eventually decomposed, it appears that there will be no new kelo trees for the lichens to colonize, which would mean local extinctions of the species dependent on kelo trees. There is likely a similar situation in many other Finnish protection areas. Loggings that cause disruptions of kelo continuities are also completed today especially in northern Finland. The continuing decline of kelo trees leads to the decline of lichens and other species dependent on kelo trees.

“Scarce kelo trees may still be found in the area, and surveying these trees made me feel like an archaeologist studying ancient relics.”

The research on the lichens on kelo trees will continue next summer. With the data we will collect then, we may look into the development of the lichen communities on kelo trees over time after their death. Previous studies have strongly suggested that the value of kelo trees for lichens increases with the time after their death, but the studies so far have been insufficient. In addition, we may look into how the lichen communities are affected by the chemical features of the wood. For example, lichen communities on bark and rock substrates are known to be strongly affected by the chemical variation of the substrate. This could also be the case for deadwood substrates, but it has not been studied.

Micarea hedlundii requires moister conditions, and thus it is not found on kelo trees in (sub)xeric pine forests. It may, however, be found at the base of kelo trees or fallen kelo trees in spruce-dominated forests, where the moisture of the substrate and the immediate surroundings is higher. Photo: A. Nirhamo

What kind of lichens do we find on kelos?

- About 1 700 species of lichens are known from Finland

- About one-third of them are epiphytic i.e. growing on trees

- About 10 % of epiphytes are found only on (dead)wood

- In addition several species grow primarily on wood, and facultatively on bark

- Out of the red-listed epiphytic lichen species, one-fourth (78 species) occur primarily on wood

- The lichens that grow on wood may coarsely be divided into species found on decaying and moist wood and species found on decay-resistant, dry wood

- For the latter, kelo trees are the most important substrate

- “Kelo species” may also be found on fences, the walls of sheds or barns, piers and other wooden structures

- About one-third of them are epiphytic i.e. growing on trees

- About 10 % of epiphytes are found only on (dead)wood

- For the latter, kelo trees are the most important substrate

Out of the lichens found on deadwood, perhaps the most startling are the calicioids, which include for example the species from the genera Chaenotheca and Calicium. Calicioids are a taxonomically disparate group, but they share similar morphological and often also ecological features. There are also non-lichenized fungi that are also referred to as calicioids, which share a similar morphology with calicioid lichens. Many calicioids (both lichenized and non-lichenized) are specialized to deadwood, and they are also characteristic for kelo trees. For example, Chaenotheca ferruginea, Calicium viride, the rare Calicium tigillare, or the non-lichenized Chaenothecopsis fennica may be found on kelo trees.

This article was written and photos were taken by Aleksi Nirhamo, our lichen specialist (you can read more about him in the People-tab)

Pem presenting in the conference

Tilla, Pem and Aleksi from the Kelo-project held presentations of their PhD-projects in the “International Research Network on Cold Forests”-conference, which was held in Joensuu this year, in the beginning of October. From down below you can watch the five minute presentations uploaded in Youtube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RemkfpW7cG4

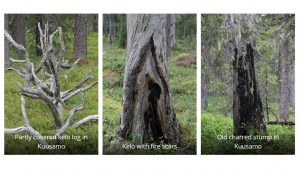

Salamanperä forest and an old charred stump

Hello, this is Pem and Tilla, working on our doctoral disserations in the Kelo-project and managing this website. We started just at the beginning of the summer. Tilla will be diving into the chemical composition of kelo trees and Pem will be focusing on the dynamics of kelo trees – how often and where they form and how long do they remain standing. Together, we aim to answer how and why some pines become kelo trees, and what are the factors responsible for creating this one-of-a-kind forest structure.

In this September evening, we have just finished our first summer of field work. Yay! We started it in the cloudberry-rich Kuusamo in northeastern Finland, continued in the steep hills and eskers of Northern Karelia, and have now wrapped up the establishment of our sample plot network in the rocky forests of Salamanperä just as autumn colours are starting to bloom in the birches and mires.

With help from Romain Bergeret (visiting us from AgroParisTech in Nancy, France), and the kelo-project’s lichen specialist Aleksi Nirhamo, we mapped kelo trees, their characteristics and peculiarities in circular sample plots inside some of the best remnants of old-growth forests still remaining in Finland. This network of field plots forms the backbone of next summer’s fieldwork, where we will sample the trees for their growth history, chemical composition, and the species that dwell on them. You can get to know all the people involved in this project through this link.

We saw some very old and remarkable kelos, in addition to multiple cut stumps and trees that had died young. It is surprising how far human influence reaches even in the most distant forests of Finland! Fires had been present in the history of most stands, and we were able to observe trees with multiple fire scars and charred surfaces. The fire history of the trees is of interest for both of our studies.

Now we will continue to develop our research methods through the winter and do some preliminary analysis from the collected data. What might we find?